On women not shutting up

Noticing what has changed since the 1990s.

When I was a teenage wannabe music journalist, I went ‘up to Dublin’ one weekend to attend an event being run for young people like me. A publication had invited journalists and experts from the print and radio worlds to tell us how to get into the industry, and in a dimly-lit city centre venue we could put our questions to them.

We all wanted to be like the cool journalists who worked for the NME, Hotpress and Smash Hits. What we wanted most of all was for people to give us the secret to a career reviewing and interviewing, a secret I’m not sure I even know the answer to now. (I suspect it’s just a love for music combined with bloodymindedness, though.) Living in suburban Cork and writing album reviews for a local freesheet, I had dreams of being just like these fancy journalists who got to hang out with bands and live in big, scary Dublin.

At one of the roundtables, I remember a journalist getting snippy with a guy over his band name, because as he pointed out, there was at least one other band in Ireland with that name too. I felt bad for that hopeful musician who was looking for some positive encouragement. Though the journalist was probably doing him a favour, it was a swift introduction to a message being delivered without any bit of people-pleasing to buffer its impact.

Then I got to another roundtable, where the lack of people-pleasing felt uncomfortably close to home.

At this table, another teenage girl asked a man working very high up in the national commercial radio business about getting into radio as a young woman.

I’ll never forget his reply: that audiences aren’t interested in female voices.

If you thought that conversation took place in the annals of time, I’m afraid I have to inform you it was the very late 1990s. The teenage me was appalled, but in one way sort of unsurprised. And I was certainly not in the position to do anything about what he said. Instead, I decided to hold a private grudge against this man, and told myself I would never let his words stop me from pursuing what I wanted to do.

I did end up getting into arts journalism, and to this day I feature regularly on the radio. I’ve never worried about whether men do or don’t want to listen to me, because anyone who doesn’t want to listen because I’m a woman isn’t worth worrying about. And I don’t really think, in this day and age, any rightminded person would hold such a bizarre viewpoint.

But I did think a lot about that other teen girl. Being on the sidelines, I had the freedom to ignore this powerful man (especially as, at that time, I was into writing and I didn’t really think about getting into radio until I was in college). But this gal had to sit there while a man with power decided to tell her that she was never going to make it because of her gender.

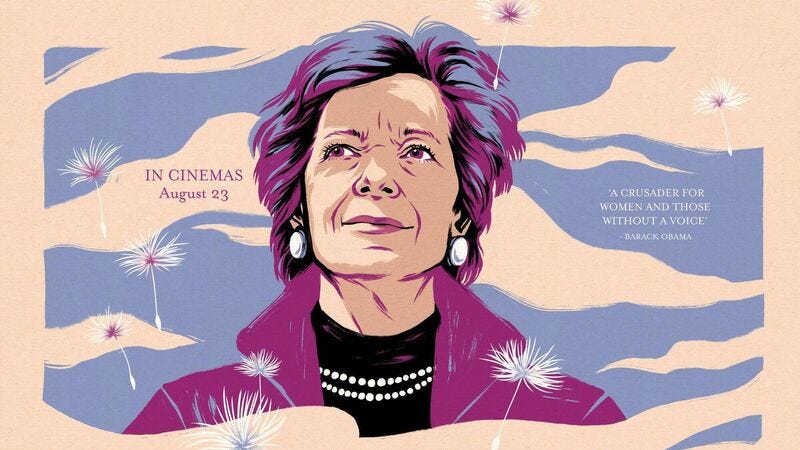

I hadn’t thought of that incident in a few years, but it resurfaced again when I spotted that the documentary Mrs Robinson (directed by Aoife Kelleher) has become the highest-grossing Irish documentary since Nothing Compares (directed by Kathryn Ferguson) in 2022.

Both documentaries are about outspoken Irish women - former President Mary Robinson and musician Sinéad O’Connor respectively - neither of whom put up and shut up. But both were told to shut up and put up throughout their careers, and both were considered just a bit too outspoken for their own good, for different though converging reasons. Both of their origin stories began long before the millennium, and long before I was a teenager trying to find her own way in the world.

But I knew of them both, of course, and I knew there was something almost illicit to what they were doing: being women in public. Women who wanted their voices to be heard.

I was so excited when Mary Robinson became President, because it showed me that women not only deserved a position like this, but they could also reach it too in the Ireland I lived in. I took a little longer to fully understand Sinéad O’Connor, but I saw that she represented something a little dangerous and transgressive, being a young woman unafraid of speaking out. I knew there was something about her that bothered people, and that it seemed to hinge on her refusal to stay quiet.

So when I heard the radio professional speaking to that teenage girl, I was able to make the link between the cultural strangeness around outspoken women’s voices, and how it could be used as a barrier against us being heard in certain spaces. Those with power could decide it was best if we weren’t listened to, and could also place the blame right at our own too-dainty feet.

I thought of that experience in my teens while reading about Mrs Robinson grossing over €100,000 at the Irish box office, because it felt so far from what that radio professional was trying to say back in 1998 or so - that people don’t want to listen to women. It turns out that people do want to listen to women, and that there is a hunger out there for the stories of Irish women who were told repeatedly to shut up - women who were pointing out this country’s flaws.

It might seem strange to Gen Z now, but there were genuine conversations and debates that happened in my youth and beyond about who actually wants to listen to women on the radio. There was often the mention of some random study that claimed that it was a definite scientific FACT that people don’t like women’s voices on radio. I’ve always suspected that as equality develops in a society, so too does the realisation that this ‘fact’ is in actuality a reflection of a social norm.

Finding out that large numbers of people are paying in to watch these documentaries and hear women speak showed me how much things have changed. Women’s stories aren’t ‘niche’ and people in Ireland are showing they want more of them. Audiences are demonstrating that they do, actually, want to listen to women speak.

As Robinson or the late O’Connor would naturally point out, this all in no way means we have reached full gender equality in Ireland, but I think it’s good to note these moments of progress when they happen. Not so we can say ‘well now, aren’t we great’, but because celebrating them helps us to see that social change can, and does, happen. But also because when we catch up to where we are, we can ask - what else needs to be consigned to the dustbin too?

I hope that the young woman at the music journalism event eventually went on to work in radio. But I also hope more than anything that if someone said the same thing to a young woman these days, they’d be rightly challenged over it. Or more likely, laughed at.

On a related note: the Irish documentary Housewife of the Year is out on 22 November. I haven’t seen it yet but its director Ciaran Cassidy is featured in Social Capital and I’m delighted to see him tackle this particular part of Irish culture of old.

When we talk about how women were seen in Irish society, you can’t get more illustrative than the Calor Housewife of the Year competition. As one woman puts it in the trailer, ‘We look back and say - why did we do that?’.

Very well said Aoife , really enjoyed your article .

Nice read, I've shared it with my daughter